The award-winning inventor Gilman Moulton worked in Boston as a bed-springs purveyor and agent for his 'Eureka' brand clothes wringers, and was in-and-out of various business in his 113 Court Street address from 1868 until 1888. Moulton had a strong inventive streak, holding a patent for an apartment air ventilator and winning many prizes at various exhibitions for his simple and clever devices. His Eureka washer won a third place medal and certificate in 1868 for its improvements in clothes-wringing technology from New York's American Institute-an association of inventors.

Moulton's planchettes are similarly inventive. Their labels list him as 'General Agent,' implying that he most likely had the items manufactured for him by an anonymous jobber, or made them himself as a side-job to his clothes-wringing business from his Waltham factory. From his storefront he wholesaled the items to booksellers and stationers in New England. We know little else of Gilman & Co, with the exception that the planchette salesman served as treasurer of his Methodist Episcopal Church in Maplewood, and that his Eureka brand wringers were party to a lawsuit against a competitor's copycat product in 1904.

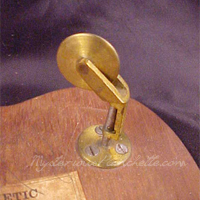

The planchettes themselves have a number of unusual features and are of a very nice quality. Shield-shaped and round-nosed, the planks have high-quality brass castors and wheels. The pencil aperture is of turned wood, and the plank is most likely of ash or walnut, with nicely-rounded edges and a middling weight not unlike a competitor's planchette from this area and period: Cottrell's Boston Planchette. The boxes are also similar to other existing brands of the period, with a dark blue hue and a simple label extolling the virtues of this 'electro-magnetic' wonder, and include a trade circular.

The topside of the board carries what is undoubtedly one of the most unique features of any planchette. A set of thin, overlapping copper and nickel plates provide a sort of 'battery' to charge users' investigations into 'powers and workings of the internal and external mind of man.' While the construction gets the basic principles of battery design right, users may have been shocked to discover that the plates served little purpose beyond what their own mind afforded them. The intention of the plates, of course, queues perfectly with the prevalent theories of animal magnetism of the period.